At the end of last year, I sat down and drew up my 2018 race calendar. It would be my first year of running ultramarathons, and I knew I wanted one race to also be a fundraiser for mental health.

The Cotswold Way Challenge seemed the perfect candidate, as the mental health charity Mind were already involved. It would be my first 100k—with a daunting 2400m of elevation—and definitely the pinnacle of my running year. As a bonus it was a point-to-point race (no loops) starting in Bath, traversing a large part of the beautiful Cotswolds, and finishing in Cheltenham.

I set up my JustGiving page and nervously started asking for donations.

In this post I’ll describe some of my preparation, particularly for the 30°C heatwave that the race took part in. In Part 2 I shared my report of the race itself.

Training

I’d run my first ultra in April, the 50-mile Butcombe Trail Ultra. It went well but I tried to train too soon afterwards and came down with something that knocked me out of any kind of training for a week.

Not only that but after I began to feel human again I had a lingering cough which lasted another 3 weeks. I couldn’t run hard without feeling like I was sucking through a straw which was slightly disconcerting. I was given an inhaler and told to come back if it didn’t go away.

Once I got back to training, things were uneventful:

- I was still managing patellar tendonitis in my right knee. This meant continuing to include plenty of cycling and not running on consecutive days.

- I re-introduced tempo and hill sprint workouts. I’d dropped both previously during injury recovery, but missed them and realised they were an important part of a well-rounded training approach. At the same time, I made sure my easy runs were definitely easy so that I could recover well from these tougher workouts.

- I did a few fasted runs (max 10km) to improve fat burning, and some full-body strength training at the gym.

- I was much more relaxed about mileage, knowing what I’d run 50 miles on, and had more faith that my mental attitude would be a big part of getting me to the finish.

Here’s how my 7-week training block looked:

So my peak week was 64km / 40 miles, and my average was 44km / 27 miles per week. This is considerably lower than your standard 100k plan might suggest, but I felt confident it was enough and was also building extra aerobic fitness through the cycling.

The dip in training around 4 June was due to my knee flaring up. I knew it needed rest, stopped training for a few days and rested up as much as possible.

This time I also managed to recce 90% of the route through a series of three increasingly long runs:

- 22km, Bath to Dryham

- 32km, Tormaton to Dursley with Nick and Dave (thanks guys!)

- 42km, Dursley to Cheltenham

Part of my training was also losing a little weight that I’d put back on through injury and, well, over-eating. I went from 68.1kg down to 66.5kg. I also bumped up my VO2 Max from a low of 49 back up to 53.

The Magic Marathon

2 weeks before race day I planned my longest training run and recce: a marathon from Dursley to the finish line Cheltenham. It was a pivotal run for me.

It did not start well.

I drove over a rock coming out of Bath and got a flat tyre, putting me behind schedule by 90 minutes. When I finally set off from Coaley Peak Picnic Area I was frustrated and constantly glancing my watch, cursing every number on the screen.

I enjoyed the long wooded descent from the picnic site but then came to a fork with both routes marked Cotswold Way. I chose the wrong way and ended up on a circular walk up a hill which took me way off route. I tried to cut back and ended up where cutting back always leaves you: climbing over barbed wire fences and swearing loudly at stinging nettles.

Maybe this wasn’t my day: I would probably cut short and stop at Painswick.

As I got back on route I realised how much the numbers on my watch—distance, pace and heart rate—were stressing me out, so in a mild rage, I deleted nearly every screen I had on display. In a radical move, my expensive new running watch now showed me the time of day.

I instantly felt better, dropped into a comfortable pace and took in more of what was around me. Spurred on by the shitty start to the day I powered through and made the marathon in great time. It felt like a big mental win.

Something else happened that day: I drank a lot less water. Instead of fussing over getting x ml per hour, I just sipped when I felt like it. Drinking enough water had become a source of anxiety for me, with the ever-looming threat of dehydration and heat exhaustion.

On this run I drank 2 litres of water over 4.5 hours in 20°C+ temperatures, which is considerably less than I’d usually drink. But I felt fine; actually better than fine. It was a revelation to me and together with some research I’d been reading on hydration it all suddenly clicked and released me of some burden I’d been carrying around unnecessarily since I started running.

When I finished and reviewed the run on Strava the pace was great and my HR was right where it should be. That it all worked out after a rubbish start, and just running by feel was a huge confidence boost.

On a less buoyant note, I also had my second issue stomaching Tailwind. Well, it was either Tailwind or eating a Chia Charge too quickly (they’re really dense!) Final strike; I wouldn’t be Tailwind-ing for the race. I did however really enjoy the Nakd bars I took…

Race preparation

With training winding down, my race preparation centred around the familiar themes of fueling, equipment, pacing, and the less familiar theme of figuring out how to run through a heatwave.

Fuelling

Based on my body weight I figured I should be aiming for 50g carbs per hour, and about 180 to 240 calories per hour.

I decided to use a mix of Nakd bars and Torq gels.

Nakd bars come in loads of different flavours, which I knew would be a big factor in being able to stomach them 5-6 hours in. They are also wholefood based: nuts mushed with dates, both of which I tolerate both very well. They are compact (thin!), widely available and really easy to eat on the go.

Each Nakd bar was around 130 calories, with 19g carbs (it varies by flavour.) I packed a few of the Peanut Delight flavours for an extra protein boost (5g per bar) later in the race.

I also wanted some gels to pack a more concentrated energy punch. After trying Torq gels a few months back, I was a big fan. So I bought a box of the Rhubarb and Custard gels. They taste amazing. Each gel contains 114 calories and 28g carbs.

Brief reflection: I initially jumped on the Tailwind bandwagon after nodding along with all the runners moaning about sickly, unnatural gels. But in truth, I’ve never actually had an issue with gels, and there are plenty that taste great. I’m happy to be using them again, as their convenience is unbeatable and the carbohydrate load is carefully optimised for performance.

I planned to eat one Nakd bar and one gel per hour:

12:00Nakd bar12:30Torq gel13:00Nakd bar13:30Torq gel- Etc…

This meant I was getting roughly 244 calories per hour, along with 47g of carbs.

I didn’t realise at the time but it was fortunate I added the gels in as the sugars in Nakd bars are primarily fructose, of which you can only process a limited amount (30g) per hour. So relying solely on the bars may have ended up slowly depleting me over time.

Gear

Since my first ultra, I’d changed some of my gear. I switched to an Ultimate Direction Ultra 4.0 vest, as my slimmer speedier Salomon vest seemed to be falling apart.

It feels a lot more sturdy, has more zips to stop things slipping out, and is still ridiculously light.

I also chose this vest because I wanted to be able to run with a water bladder. I got a 1.5L bladder and decided I would also carry one 500ml soft flask. I froze the soft flask the night before so it would be cool against my chest, and left the filled bladder in the fridge too.

I wanted to run in my Hoka One One Speedgoats but packed my Brooks PureGrits to switch into at halfway as they have more width than the rather narrow Speedgoats, and I suspected my feet might have swelled by then.

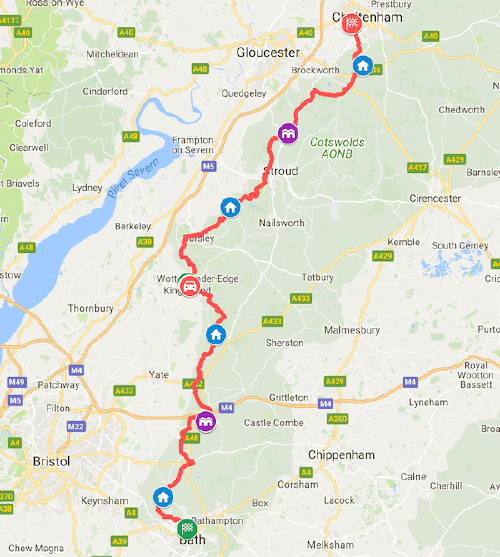

I got a great tracking setup in place for the family by sharing my location in real-time via Trusted Contacts (available on iOS and Android) and then saving the race route in Google Maps.

Now, when you open up Trusted Contacts you can ‘Open in Maps’ which will then show your location, with the route also marked out:

If you can’t see the route you need to go to My Places in Google Maps to ensure it’s loaded and enabled. If it’s not in My Places / Saved then you didn’t save/favourite it properly.

It beats trying to match a location to a separate map, but the downside is that the tracking is not great and can lag or jump at times. Apparently, I was on the M5 at some point. I don’t know anything about that.

After my marathon success, I updated my watch screens. My main watch face would again just be the time of day. I knew the distance and location of all the rest stops and didn’t see the need for anything else.

I had other screens that could show pace, average pace, total distance or heart rate when necessary. As it turned out, I stuck with the time of day for 99% of the race. I loved it. I didn’t want to see anything else, and it helped me avoid the number gloom that creeps in as you inevitably slow towards the end.

The Heatwave

With all my preparation in place, I was feeling pretty confident and excited to get out and run this course.

But with 2 weeks to go, the weather reports started rolling in: Heatwave.

Hopefully that’s the last time I’ll ever share a weather headline from the Express.

I have never been a fan of running in the heat, and the thought of running farther than ever before through the peak of a heatwave was nothing short of nightmarish.

Temperatures were regularly sitting at 27°C, and peaking at 30°C in places.

In my head my chances of finishing dropped from 90% to 50/50.

I felt angry. I’d been waiting for this day for 7 months: why a bloody heatwave now? I also felt scared, knowing that running in heat all day would likely trigger physical anxieties around overheating and dehydration.

After some quality sulking, I decided the heat was something I could get smart about, just like any other aspect of running. I knew runners across the pond routinely ran longer races in insane 40C+ temperatures. How did they do it?

I started reading everything I could find, and learned a lot.

Changing Body, Challenging Beliefs

As with so many things, limited exposure is effective in acclimatising to the heat. Getting out in the Sun sends your body the signal to start adapting to it:

There is plenty of research to show physical adaptations occur with repeated heat exposure: increased plasma volume, increased cardiac output, increased sweat rate, and decreased sweat sodium concentrations to name a few.

I started doing my final runs in the midday heat, allowing my body to get busy on the physical adaptations, whilst I psychologically acclimatised to what it’s like to run in an outdoor oven.

In another important long run, I realised that the biggest threats to my race were not the physical aspects of heat—I knew how to stay hydrated, cool and scale back my pace—but the psychological fear it was putting me through. I got a clear glimpse of the old belief that “I cannot run well in heat”, and dropped it as I hurtled down a hill in 25°C on my last long run.

Along with dropping that belief, I focused a little more on the positives: the Sun makes everything beautiful. The route is going to be stunning, your kit will be light, and there will be none of that soul-sucking mud you suffered through for 6 months.

Do Not Sweat It

To succeed in the race I needed to keep my core body temperature down. A rising core temperature would increase the risk of heat exhaustion and digestive issues.

Understanding thermoregulation was much more interesting than I anticipated, as it gets to the heart of why humans are natural born runners.

I developed a questionable fascination with sweat. Sweat is the primary reason humans are the best long-distance runners around. Other animals sweat too, but rely primarily on panting or other methods to manage their temperature:

Humans, uniquely, can run long distances in hot, arid conditions that cause hyperthermia in other mammals, largely because we have become specialised sweaters. By losing almost all our body fur and increasing the number and density of eccrine sweat glands, humans use evapotranspiration to dissipate heat rapidly, but at the expense of high water and salt demands. In contrast, other mammals cool the body by relying on panting, which interferes with respiration, especially during galloping which requires 1:1 coupling of breathing and locomotion.

That coupling means that most animal needs to slow down or stop to cool down, whereas us sweaty, bare-chested humans have escaped that limitation, as the sweat continues to cool our bodies independent of pace.

Some scientists believe these adaptations formed a pivotal part of our evolution, a theory known as the endurance running hypothesis.

Stay Wet

I learned that you can essentially mimic the heat-evaporating qualities of sweat by staying as wet as possible. I read a summary of Pam Smith’s preparation for her shock Western States win in 2013 and she drilled this home.

When I say Stay Wet I’m not talking about a little trickle over your head: you want to be a soggy dripping mess. Pam’s instruction to her crew on the day of her win was: “Treat me like a Porn Star: keep me wet, keep me lubed, and keep me excited.”

A key point to remember is that external cooling is a much more effective means of cooling the body than drinking water. What’s more, the advice to drink voluminous amounts of water in the heat (regardless of thirst) increases the risk of hyponatremia.

Cool the Right Bits

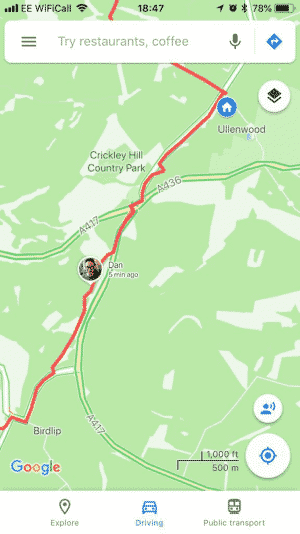

Pam’s report also got me familiar with the body’s cooling points:

Cooling points are simply areas where your blood flows close to the surface of your skin. They’re useful to anyone looking to stay cool, but particularly to endurance athletes who will be exerting themselves for hours on end.

When you are exerting yourself in the heat, your body will be diverting blood away from areas like the belly, slowing digestion, so that it can send it to the skin to release some heat. You can help this process along.

As you can see from the image, two of the key cooling points are the back of your neck and your wrists.

Because the blood flows so close to the skin in these areas, we can apply external cooling to quickly “chill” the blood, allowing it to recycle and transfer more heat from the core of the body to the skin surface. You can apply external cooling in many ways, like putting a wet bandana around your wrist.

One of the most effective cooling points is the neck, which leads me nicely on to…

The Ice Bandana

I’d just followed the 2018 Western States (Go Jim!) and noticed once again that a lot of the runners had ice stuffed into bandanas which they wore around their necks.

I was not running in Western States temperatures but I knew that if I could get ice on the course it would be a big help. After enquiring, the organisers unsurprisingly told me that there would be none available. Not many freezers on the Cotswold Way.

Fortunately a week before the race, my Dad had very generously offered to crew for me all day, and would be able to ship around some ice in a cool box. Winner!

Now I just needed to figure out how the WS runners put ice in their bandanas without it falling out. It turns out it’s pretty easy to make your own ice bandana. I followed this very simple guide after buying an over-priced but speedily delivered bandana from Amazon.

I’m holding open the 6" opening at each end where you feed the ice in. Then you just need to hold both ends and spin like a skipping rope to close the gaps before tieing around your neck.

The day before my race I listened to a podcast interview with Ian Sharman. He’s a Brit who just landed his 9th consecutive top 10 finish at Western States, a pretty phenomenal achievement. He went as far as to suggest that Western States wouldn’t be possible without ice, or at least not at the elite paces we see each year.

Dress for the Sun

White clothing works well for reflecting some solar light (although this is disputed). My running wardrobe is predominantly black so I bought a white Under Armour singlet. I did have a running vest from Mind, but it was dark and rubbed under my arms, so I saved it for the last 7k leg.

Hats are also important to keep the sun off of your head. I already had a few hats, but several people from the UK Ultra Runners Facebook group recommended a white bucket hat (think Kevin & Perry), the ultimate in runner sex-appeal. I bought one in case.

Drink to Thirst

Hydration is a controversial area but for now, I will just share this quote from Tim Noakes:

Now, dehydration is not a disease, and it only has one symptom, and that is thirst. If you start to exercise, and you don’t drink, after a period of time, you will become thirsty—that’s your body’s way of telling you to drink. The idea that you should drink ahead of thirst is absolutely nonsensical. As I’ve said, we’ve evolved from other creatures. We don’t need to be told when to drink. They regulated their fluid purely by thirst. So why should humans be different from every other creature on earth to be told when and how to drink? The reality is you don’t need to be told when and how much to drink. We have a 300 million year developed system that tells you with exquisite accuracy how much you need to drink and when you need to drink. It’s called thirst. If you rely on thirst you won’t ever become dehydrated, and you won’t also ever become overhydrated.

I am yet to see anyone qualified effectively counter Noakes’ views on hydration and electrolytes, despite the fact that his recommendations do not line up with what many recommend (although that is changing.)

After my own experiments, and finding Ian Sharman on the same page, I felt confident that drinking to thirst would be enough.

Noakes also argues that salt pills are unnecessary for balancing salt levels (the body does fine on its own), but it seems likely there are other benefits to taking sodium, so I packed a few pills in case, and because there was no downside to taking one if I felt bad.

Staying easy

Rather than obsess over water and electrolytes, I would focus simply on not pushing too hard in the first place.

Controlling pace is key in not pushing your temperatures high. It sounds simple, but it’s often overlooked.

The more I read about dehydration, cramps and the like, the more it made sense for that their cause was simply pushing too hard: over-exertion. People often claim relief from these issues by eating or drinking x, but think about what they’re also doing at the same time: slowing down, taking a break.

I had no fixed pace in mind, but had a good sense of what easy was for me. Something I read a while ago has stuck in my head since:

Easy is not a speed, but a state of mind.

Trust Me on The Sunscreen

Re-apply sunscreen, liberally. There is no evidence that it helps with cooling, but you need to protect against the acute inflammatory response that is sun burn. Your body will be inflamed enough through muscle damage!

One coat at the start isn’t enough. You’ll need to top up at checkpoints along the way if it’s hot. I used a cheap waterproof SPF 50.

Pacing

I had no intention of setting paces to run by, but as my Dad needed to plan his day to meet me at all stops I tried to put some rough times together.

I guessed an average pace of 6:45 min/km for the first 50k. My easy ultra pace over hilly terrain is about 6:30 min/km, but I added some extra for rest stops and hill walking.

I assumed my pace would drop off in the second half with the heat approaching 30C, so estimated that my average pace would drop to 8:00 min/km. (Except for the last 7km which I knew would be faster as it was all downhill and I’d be psyched to finish!)

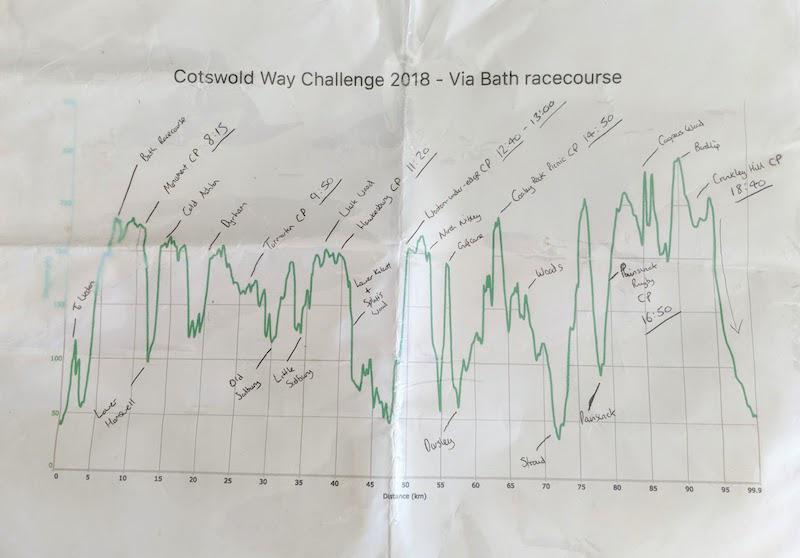

I ended up with these times:

07:00— START from Royal Crescent, Bath08:15— Sir Bevil Grenville’s Monument Field (11km total)09:50— Tormarton: West Littleton Down (26km total)11:20— Hawkesbury: Hawkesbury Upton Village Hall (38km total)13:00— Wotton-under-Edge: Wotton Sports Centre (50km total)14:50— Coaley Peak Picnic Site and Viewpoint (64km total)16:50— Painswick RFC and Sports Club (79km total)18:40— Crinkley Hill: Ullenwood (93km total)19:25— FINISH at Dean Close School, Cheltenham (100km total)

Looking over last years results I realised a 19:25pm finish would put me somewhere in the top 10! That seemed unlikely but I trusted the pace calculations.

I tapered off the week before and took the usual two days off before the race. Each day off the temperatures pushed higher and I wished I could spend more time training in the heat. But I stayed put with my drip of Innocent smoothies and wondered how I was going to pull off the longest, hilliest and hottest run of my life.

Part 2 is now live! Find out how the Cotswold Way Challenge worked out for me.

Get my sharpest ideas, once a week.

I publish every day on fitness, tech, wisdom & learning, drawing on my experience as a founder, coach & meditator. I distill the best insights every Wednesday: