How to run 50 miles. It’s probably not a question that keeps most people up a night. But it’s something I’ve wanted to do for the last year.

These two posts are a detailed rundown of my preparation and experience of my first ultramarathon, as well as an informal and hopefully entertaining guide for anyone looking to run 50 miles, or just push their running further.

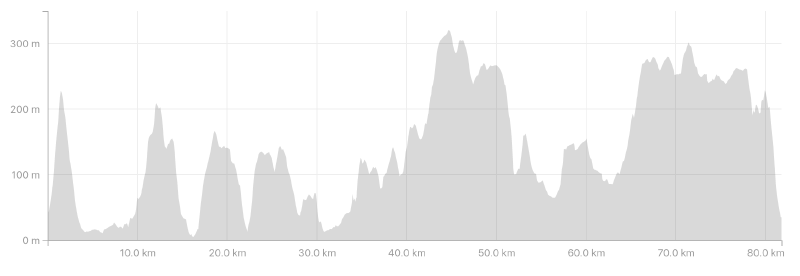

The Butcombe Trail Ultramarathon (BTU) is a 50-mile loop that visits 6 pubs on the Mendips. It’s mostly off-road and pretty hilly, clocking in at over 1500m of ascent with some very steep climbs. Part 2 covers my experience of the race itself.

Background

Like many ultra-nuts, my thirst for running distances beyond the marathon came from reading Born to Run by Christopher McDougall. I was captivated by the allure of ultra running—the adventure, the autonomy, the hero’s struggle, and the community.

It was sometime around the start of 2017, and the problem with going beyond the marathon was that I hadn’t run a marathon in the first place. I had just started running half-marathons, after finishing my first 10k in Summer 2016. I was really getting into running, but taking on an ultra seemed pretty far-fetched at this time.

Regardless, I continued to rack up my mileage and constantly pushed my long runs further, all the while enjoying it more and more. I ran a few other races before finally completing my first marathon in October 2017—The Eden Project Marathon. I had a great day out, but more importantly I was now lined up to tackle the events I really wanted to run.

I ran one other race in November 2017—The Bath Hilly Half—and took a nasty fall on a cobbled downhill. My right knee took the brunt of the impact, and I was left with what looked like a second knee-cap, and a scar right across the patellar tendon. It really hurt, but after a week of taking it easy I was happily running again, and started to ramp up my mileage further.

2018 was to be my year of going ultra. I booked in my main races:

- The super hilly CTS South Devon Marathon in February

- The 45 mile Green Man Ultra around Bristol in March

- The 100k Cotswold Way Challenge from Bath to Cheltenham in June

The 100k was to be something special to me—a sponsored run for a cause I cared about: mental health. The mental health charity Mind was already involved with the event, so it worked out perfectly. As a bonus the race started at the Royal Crescent in Bath, which felt like a second home having lived in or around Bath for some years. You can read more about my personal reasons for fundraising here.

Training went well. I ran 5-6 times a week, and followed the basic recommendations of increasing mileage, extending long runs and getting comfortable eating on the move. I stuck to trails as much as possible, included lots of hills, and sprinkled in tempo runs or sprints when I felt like it. It wasn’t much different to training for a marathon, besides the long runs getting a bit longer.

But after a solid block of training around December/January—including recce-ing most of the Green Man route, and landing my first 50 mile weeks—my right knee began to ache. It was subtle at first, and I thought little of it. The CTS South Devon Marathon was coming up, and I wanted to carry on training. I’d give it an extra day or two of rest before the run.

Injury

But the pain became more intense, and in a later run I struggled to finish an easy-paced 10k run. I went to a physio who diagnosed patellar tendonitis, with a lot of compensatory tightness. As he advised, I took some rest, and then tried starting with really small runs again, with a day or so in between to give the tendon an opportunity to de-load.

However, the marathon was that weekend. I rested most of that week and decided to give it a little test run on Friday to see if it was any better.

I didn’t need the test run. My knee wasn’t ready to run 5k, let alone a marathon along coastal cliffs.

I gave up on the marathon. It’s no fun missing your first race of the season, but I would save myself for my first ultra: Green Man. I had 4 weeks.

Rehab

Meanwhile, I was working hard cross-training, k-taping my knee regularly, applying heat once or twice a day to stimulate blood flow, foam rolling, and doing some extended static stretching to ensure my hamstrings, hip flexors, quads and calves were not tightening up around the knee.

Despite all the rehab, the pain continued at the same intensity. It always showed up, haunting me within a few minutes of starting running. It felt like the bones above and below the knee were literally grinding against each, and the whole joint would eventually feel stiff, painful and progressively more difficult to move. It would happen every time I tried running and pretty soon I couldn’t ever imagine running without that gnawing, dull ache. It was really depressing.

After a few more rests and restarts, and with Green Man a week or so away, I saw another physio. Why wasn’t I getting better?! He confirmed the same diagnosis and told me to stop running, for 2-3 weeks. I had to give up on the idea of Green Man and felt despondent. (It was later cancelled due to the snow.)

As well as missing my first ultra—and my home ultra!—I now had nothing booked in before supposedly running 100 kilometres. What on Earth had I signed up for? Donations kept coming in, whilst I was sat at home completely incapable of completing a parkrun, let alone an ultramarathon.

Around this time I saw a mention of Butcombe Trail Ultra tickets getting low on Facebook. I was aware of the race but thought it looked hard as nails—50 miles and a lot of elevation.

As a contingency, and on the off-chance the knee got better real soon, I bought a ticket. Around this time I also booked in an MRI to check there was no deeper damage to the knee, as I’d become convinced something more fundamental was going on.

Injury sucks in so many ways, but one under-appreciated kick in the nuts was that my body decided it still wanted to eat 3000+ calories a day, even when I wasn’t running. Cue weight gain, and then trying to compensate by cross-training my brains out.

A New Hope

As the 3 weeks of running rest came to an end, I had actually stopped obsessing so much. I was enjoying cycling and strength training and felt some superficial peace with maybe not being able to run. I could feel that the knee was tender even outside of training, and had all but given up on running much of anything.

With BTU about 45 days away, I went for a short run. Despite my knee aching before the run, the deep gnawing pain didn’t show up. And it felt better afterwards!

It sounded too good to be true, and I didn’t dare believe it. I gave it a day of rest before trying another run. Still good! Each time I ran, I made sure I cross-trained the next day.

At the end of March, I ran my first 10k in 2 months. It felt good, but my knee was still stiff, my other muscles were still compensating around it. I was also very aware that I needed a lot more than 10k under my belt to line up for 50 miles of the Mendips.

Around this time, my MRI scan results came back:

As I had guessed with my recent running successes, the MRI came back generally positive. It confirmed the tendonitis, but also revealed a split right down the middle of my patellar tendon (!!!), likely from my fall in the Bath Hilly Half. But there was no further action required. I just had to be a responsible athlete and not trash it.

So it seems that the fall in November probably damaged the tendon (as well as the underlying fat pad), which then weakened the whole area, thus making the patellar tendon more susceptible to tendonitis as I ramped up my miles over the new year. Tendons are slow movers and take time to heal.

But mine was finally on the mend.

How to Run 50 Miles

That’s all good well, and but how do you run 50 miles?! Let’s take a tour through some of the common advice in readying yourself for an Ultramarathon.

1) Plan ahead

You should book and plan your race far in advance, so you can train appropriately.

I mean, I didn’t plan to run this race until a month before, but this is great advice!

2) Recce the route

If you live near by, get out on the course! Most ultras are on public footpaths that you can explore any time.

This will mean you feel a lot more confident on the day. The good news is that I did live near the course 🎉 The bad news is that I still didn’t recce any of the route.

I spent all my recce time on the Green man route, covering every inch of a race which I could not start, and which was then cancelled anyway (small consolation).

As much as I’d have loved to run the route beforehand, I just ran out of time. See 1).

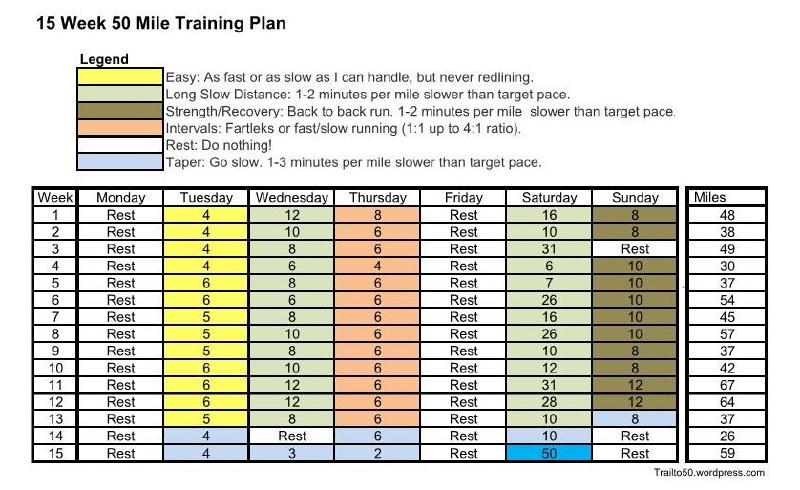

3) Follow a training plan

Here’s what a standard 50 mile plan looks like:

Here’s what my training looked like (in Strava graph land):

That’s 4 weeks of deteriorating running (not all visible), 3 weeks of no running at all, and then 6 weeks of running every other day:

- Week 1: 11km

- Week 2: 18km

- Week 3: 29km

- Week 4: 45km

- Week 5: 56km

- Week 6 (taper): 44km

My peak week was 34 miles / 56km. My longest run was 20 miles, and in fact, this was the furthest I’d run all year due to the injury. I alternated running with cycling and strength training so that whenever possible I avoided running two days in a row. I was terrified of overloading the tendon again and going backwards.

As a side note, even many of the more experienced athletes I follow on Strava seem to end up with mileage graphs that look more like the elevation profiles of the races they’re running, compared to consistent month-on-month high mileages of make-belief training plans.

I certainly don’t want to discourage people from planning their training, but many of the plans you’ll find on the Internet are very cookie-cutter, very specific to whoever devised them, assume you will be doing nothing but running, and make other assumptions about the time you have available, and that you will be able to handle repeated back-to-back weekend runs. (These are seriously tough going.)

By all means experiment, but be aware that many people prepare for ultras with very different training approaches that may include considerably less volume, different sports (swimming, cycling) and a whole lot more time for rest.

If we were to give my training approach a name, it would be closer to a 6-week marathon training plan.

What really mattered was that:

I got six weeks of consecutive training in leading up to the race. They were nervous weeks, as I had to be very wary of increasing mileage, while also being aware that I really needed more mileage. I kept up the regime of applying heat to my knee, foam rolling and stretching, each day.

I was strict in these six weeks, by removing other training stressors: no hill sprints, no other HIIT, very few tempo runs, no fasted training. Eating lots before and after training to ensure a quick recovery. Sticking at an easy pace but still including plenty of hills. Hill work is non-negotiable when the elevation profile of your race looks like this:

- I had run a block of higher mileage weeks over the New Year, so that gave me a lot of confidence that my body could do more, when not fighting off injuries.

4) Pay attention to pace and cut-offs

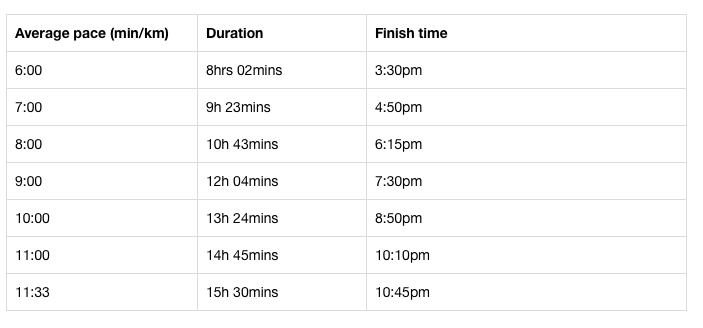

Leading up to the race, I sat down and calculated which average paces would lead to which finish times. I wanted to be prepared unless my knee starting hurting and I had to walk large segments. Even if I finished slow, I wanted the all-day experience before entering an even tougher ultra.

I also measured my walking and hill-hiking paces to have some idea of how they would affect my times. You can do this easily if you practice walking hills in long runs. All in all, the 15.5-hour cut-off seemed generous, but I wanted to know my margins should the shit hit the fan.

Most watches can show average pace, which will help you get a sense of your overall progress and some ballpark of your finish time.

5) Try everything in training first

The excellent fellrnr.com calls this the Golden Rule of Racing:

Never do something in a race you have not practised in training

Your long runs are your testing ground for anything you plan to use in a race. It’s better to discover that your shoes are rubbing 1 hour into a training run, rather than one hour into a 10-hour race.

So test the lot: your shoes, your socks, the fluids and gels you’ll be consuming, the pants you’ll be wearing, your sunglasses (maybe they constantly slip?), your lucky charm etc etc. Any small issue will be magnified a hundred times over the ultra distance, and make you a sad, grumpy runner.

For my last “full gear” long run, the week before the event, I even brought my car key along and practised charging my watch on the run.

Yes, you can charge a Garmin Forerunner 235 whilst running, which helps you get around the ~9 hour battery life.

I used the Anker PowerCore 5000 charger and carried two cables: a small USB-C cable to charge my Pixel 2 if necessary, and the standard Garmin clip for my watch. These were tucked in the back of my running belt. When charging I recommend the following:

- Lock the watch! Important so that no buttons get mashed in your pocket. This doesn’t affect the activity recording.

- Take watch off, clip it onto charge, and then wrap the watch around the charger.

- Tuck the lot back into your belt. Keep running and nervously looking at your naked wrist.

It doesn’t take that long to charge. At the end of the run, the only difference you’ll see is a period without HR data, but it doesn’t affect your averages.

On my final trial run, I also wore a relatively new running belt that I’d been testing. To my horror, I found that it was hanging by a thread after a 20-mile run.

It would surely have snapped mid-race if I hadn’t tested it out properly beforehand. As a heads up, it was this belt that broke. I replaced it with this waist belt. I’ve had no issues with the new belt; it’s secure, comfortable and doesn’t rub.

My kit

Whilst one of the things that draws me to running is the ability to just lace up and run off into the horizon, an ultra tends to involve a lot more gear. Especially when it’s your first ultra, and you panic pack.

And to be honest, I am a total nerd when it comes to playing with the kit, figuring out how to pack it all, and experimenting with different fueling & hydration methods.

I could probably have trimmed some of my kit down quite a bit, but I wanted to be prepared for a full day out—15 hours, if my knee started hurting and I had to walk—and be totally self-supported, except for extra water. I’d rather be slightly over-prepared for 50 miles of running.

Watch: Garmin Forerunner 235

Not much to say about this guy, except that I have tan lines from where he lives on my wrist. I mainly use it to see:

- Distance covered. Duh.

- Heart rate. Useful for trying to stay in Z2, below threshold, which is roughly 120-155 beats per minute. The zones are colour-coded on the watch which makes this easy to see at a glance.

- Current pace, for not shooting off like a wild stallion, and generally staying slow and steady.

- Average pace, which allows for a rough sense of progression and finishing time.

Shoes: Hoka One One Speedgoats

A shoe which I openly loathed since getting into the idea of minimal footwear. That changed when I got injured. At that point, I would have peddled drugs or performed blood magic to get better. But more promising than those two options was the idea of some serious padding to allow me to ramp up my miles with as little impact as possible.

They’ve grown on me. They’re incredibly light, and although I miss the proprioception of a lighter shoe, I still feel pretty stable on the trails.

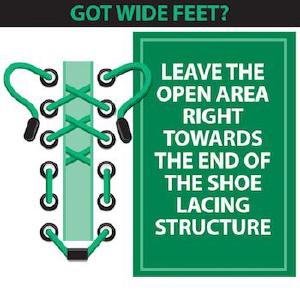

However, they are a little narrow, and I have wide feet. So they rubbed my arches after 10km. After some investigation, I replaced the insoles, and then applied some ENGO patches to both the insole and inside of the shoe, to reduce friction. These patches are expensive but brilliant, as they attach to the shoe, rather than your foot. (See the 2-Patch Technique)

I also re-laced them give a little extra room in the toe box area:

Addendum: Of course, this is England. The day before the race, after several relatively warm dry days, it bucketed it down. All day. The predicted temperatures dropped, and I got nervous and switched to a wildly different shoe: my Inov-8 X-Talon 212’s 🙈

They have a very aggressive spiked outsole for mud. I was envisioning a 10-hour mud bath, and I knew from experience that the Speedgoats turn into Speedskates when there’s real mud underfoot. Stay tuned for the race report to see how they worked out!

Vest: Salomon S-LAB Sense Ultra 8 vest

The only running vest I’ve ever used. Expensive, but light, fits like a second skin, and no rubbing. It is, however, a little fragile in my experience. I’ve had a few rips and cord snaps since using it, but it’s otherwise a great bit of kit.

Here it is, packed with all my gear for the day:

Top centre: Clear bag contains mostly required gear that I don’t expect to use: foil blanket, compass, head torch, spare batteries, gloves, Buff, long-sleeved top, spare socks and a highly suspicious bag of white powder: SIS Rego. Pour into water for optimal post-race recovery (protein + fast-acting carbohydrates), and just because it tastes so damn good, and boy will I not be wanting to drink more Tailwind at the finish. Stuff sack contains a pair of Montane Minimus waterproof trousers.

Bottom right, skin-care central: sun cream with plastered edges, as for some reason all travel-size tube edges are sharper than a chefs knife. Bodyglide for any rubbing or chafing. Clear bag contains various plasters, blister patches, anti-septic wipes and some pre-cut K tape.

Bottom centre: stuff sack contains Montane Minimus waterproof jacket.

Bottom left, pootingency kit: anti bac, toilet paper & poo bags. You know, in case you come across some dog mess and want to clear it up 🙄

Top right, drugs cabinet:

- Pro Plus. Humble caffeine is probably the ultimate performance enhancer. I can’t take too much because it makes me anxious, but Pro Plus lets me take exactly 50mg in a pill, and stay more easily aware of my total ingested caffeine.

- Ibuprofen. I have only taken Ibuprofen once on a long run before, and I try and avoid it unless it’s really necessary.

- Imodium in case of disaster pants. Not happened to date 🤞🏻

- SIS Hydro tabs in case I need an electrolyte boost, and/or some different flavours.

- Rennie, in case of any reflux or heartburn. Never had to take any before, but have also not spent a whole day drinking liquid glucose before so…

- Spare contacts 👀

Left and right centre: 14 sachets Tailwind & 2 SIS isotonic gels. While the thought of being in a place where I needed the full 15.5 hours of fuel was not pleasant, I wanted to be prepared in any case.

As a brief fuel primer, the recommendation is to try and take on 30–60g of carbohydrate an hour, which is something like 100-250kcals. (You can train yourself to take on more, but we’re talking basic requirements here.) You can get by without any additional fuel for the first 90-120 minutes of training, but that doesn’t seem to be recommended on race day because you need to be getting calories in early while your stomach is happy.

Each Tailwind sachet contains 50g carbs, clocking in at 200kcals. So I was carrying about 2800kcals of Tailwind in total. I would likely be burning closer to 7,000 calories that day, but it’s normal for your body to burn up more than you can replenish.

Front of vest: 2 Salomon soft flasks. I love these. They compress as you drink from them, so there’s no sloshing. And I needed two because some legs were 10 miles, requiring more than 500ml of water. The other pockets at the front would stay relatively free for maps (kept in a plastic wallet for waterproofing) and Veloforte bites:

These are delicious. I originally bought them for cycling, but began testing them in long runs to great effect. They are really dense, based on whole foods and easy to carry. At 60kcal a pre-cut bite, I think they are well suited to an ultra, with some welcome crunch and texture.

I also had a Salomon collapsable cup in a front pocket. “Salomon collapsable cup” is what happens when you’re up late on Amazon worrying about a race. Spoiler alert: it never left that pocket.

Besides all that, I had my separate running belt for my phone and charger. I could probably have stuffed the phone and charger into the vest too, but I’ve found in the past that they can cause weight imbalances and then the straps start rubbing.

Randoms:

- My phone was a Pixel 2, and I downloaded the free GPX Viewer app to display the BTU .gpx map file. This app worked really well.

- I had my knee K-taped to provide extra support.

- I had some instant ice packs in the car for any swelling at the finish.

- Whistle! There was one attached to my vest. It was part of the required kit. The trick is to blow on it really hard when you see a runner who looks sleepy.

Tapers & Carbs

Despite many athletes still using it, the traditional carb starve and refeed (“carbo-loading”) doesn’t have a lot of convincing evidence to support it. The good news is that you can cut out the unpleasant deprivation stage, and just simply eat a carbohydrate-rich diet for a few days before your race.

That doesn’t mean a week of binging: sometimes you can hit maximum stored glycogen in just 24 hours. That particular study concluded that “that combining physical inactivity with a high intake of carbohydrate enables trained athletes to attain maximal muscle glycogen contents within only 24 h.”

Rather than trying to cram a much higher ratio of carbohydrate than I am used to one day before the race, I took Thursday and Friday as heavenly no-carbs-barred days. These were also my two rest days before the race (my last run was Wednesday).

My advice is to stick with basics. This isn’t the time to overwhelm your GI tract with exotic sweet delicacies or 20 new E numbers. I bought the following to supplement my existing carb staples (porridge, home-made bread, potatoes, rice etc), and ate little and often between my main meals:

As I was desperately trying to get in as many miles as I could before the race, I didn’t taper my mileage that much: my week prior to the race was 44km, compared to the 56km peak the week before. I took two days of complete rest (just dog walking) before the race itself.

Race Principles

So my preparation was haphazard. My knee felt better, but I didn’t know if it would hold up over 50 miles. Even when the preparation is good, planning an ultra can get really complicated.

With so much swimming around your head, it’s good to have a few phrases that you can recall during the race to get you to the finish: simple maxims to return to when you’re confused, hurting, and wanting to stop.

1) Keep moving forward. It doesn’t matter if it’s gliding, crawling, cartwheeling or sprinting: just keep. moving. forward. You are a tiny dot moving slowly through a giant course. Your wonderful downhill form matters less than the fact that your dot maintains its glacial march through the checkpoints. Unless you are fighting a tough cut-off, what’s primary is that you just keep. moving. forward.

2) Run easy. This is a form reminder for me: to slow, to sink into my hips, to lean in and let gravity do most of the work. And to relax. There’s a marked difference between running with the trail, compared to stamping your way through it to try and maintain some ideal pace.

A phrase that I’d read a few weeks before stuck in my head: ‘When you run on the earth and with the earth, you can run forever.’

When it’s working, it feels like the legs quickly adapting to the terrain underfoot, almost caressing it with footfall. Imagine the duck, legs fluttering underneath, whilst retaining stability above water. This comes through a high cadence, which is probably the biggest change you can make to improve running economy. Hips are stable and the upper body is upright with arms flying out when necessary to assist in balance. Watch someone like Killian Jornet run.

3) Drink a bottle an hour. The beauty of Tailwind is that it simplifies fuelling down to one directive: drink a bottle an hour. For me, one bottle is 500ml water mixed with one sachet of Tailwind. This ensures 200kcal per hour, as well as covering any electrolyte needs. Job’s a good un.

With everything packed and prepared, there was only one thing left to do: repack it all, doubt various key decisions, check the weather 27 times… and then run the race!

Read Part 2 and find out how it all went down on the day.

5 May 2018